Infection: A General Idea of the Virus

# Context – “The key to contemporary consumer culture is the copyright: without the copyright and the sanctity of (individual and/or corporate) authorship, today’s mega-economics would collapse – Imagine Microsoft, for example, without copyright. Museums act as symbolic keepers of the virtue of copyright, and an art expert’s opinion on the authenticity of a work can send values soaring or crashing by vast amounts of money.” (Bronson, Copyright, Cash, and Crowd Control: Art and Economy in the Work of General Idea 2003) – “William Burroughs once told me that Kodak’s copyrighted yellow is an example of image virus: the colour carries the meaning of the product, no matter where one sees it; all objects of this particular yellow are infected with this corporate message. Similarly, when TIME-LIFE sued FILE for simulation of LIFE, we discovered they held copyright on ‘white block lettering on a red parallelogram’.” (Bronson, Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus: General Idea's Bookshelf 1967-1975 1997) – “Control is thus central to these decades’ imaginary, and it is precisely against this paradigm of control that the counterculture and hippie movement of the 1960s and 1970s will try to free mind and body.” (Patoine 2019)[1]

[1]

This conversation is inserted in the origins of what Deleuze called Societies

of Control, which administrate, through “informatic machines, computers”,

and data mining, concepts like freedom, democracy, truth, human rights, and

equity, among others (Deleuze 2006). As AA Bronson notices, in contemporary

societies “the shameless breed of our owners is formed” through ideas of “corporate

and individual authorship and copyright”, for power now resides in the

ownership of information, content, or data as well as in the capacity to sell

these statistics (Deleuze 2006). But what interest the most here, is

how General Idea launched this conversation into the art world by simulating

and infecting the contemporary consumer culture within museums and galleries,

thus exposing the hypocrisy of this institutions, and expanding their own range

of action as glamourous artists. In fact, their methodologies took from mass

media communications and commerce to uncover the real interest of the cultural

economy while shapeshifting their artists’ figure.

# Set up – We abandoned bona fide cultural terrorism, then, and replaced it with viral methods. We realized that the structure and surplus of our society was such that we could live, like parasites, on the body of our host, off the excess.” (Bronson, Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus: General Idea's Bookshelf 1967-1975 1997) – “These boys are preparing to free North America and Western Europe from the “police machine and all its records” and “all dogmatic verbal systems” (139-140). This loose narrative is constituted by a variety of images intermeshed with first- and third-person testimonies: sepia photographs in gilded books (memorabilia from the American 1890s and 1920s), the recurring “penny arcade show” but also military films from the 1970s and 80s.” (Patoine 2019) – “We knew that we had no entrée through the front door of museums and galleries into the world of glamour that seduced us, and we chose instead the viral method: utilizing the distribution and communication forms of mass media and specifically of the cultural world, we could infect the mainstream with our mutations, and stretch that social fabric.” (Bronson, Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus: General Idea's Bookshelf 1967-1975 1997) – “General Idea was at once complicit in and critical of the mechanisms and strategies that joint art and commerce, a sort of mole in the art world. Our ability to live and act in contradiction defined our work: we were simultaneously fascinated and repulsed by the mechanisms of today’s cultural economy. We injected ourselves into the mainstream of this infectious culture, and lived, as parasites, off our monstrous host.” (Bronson, Copyright, Cash, and Crowd Control: Art and Economy in the Work of General Idea 2003)

# Claim – “We believed in a free economy, in the abolition of copyright, and in a grassroots horizontal structure that prefigured the internet.” (Bronson, Copyright, Cash, and Crowd Control: Art and Economy in the Work of General Idea 2003) – “Like the work of the Fluxus artists, whom we soon met, our low-cost multiples were intended to bypass the gallery system, that economy of added value, and to travel through the more alternative audience of students, artists, writers, rock ’n’ roll fans, new music types, trendoids, and media addicts.” (Bronson, Copyright, Cash, and Crowd Control: Art and Economy in the Work of General Idea 2003) – “‘Truth to tell, the best weapon against myth is perhaps to mythify it in its turn, and to produce an artificial myth: and this reconstituted myth will in fact be a mythology. Since myth robs language of something, why not rob myth?’ (p. 135) Roland Barthes: Mythologies. Jonathan Cape, London, 1972. First English edition.” (Bronson, Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus: General Idea's Bookshelf 1967-1975 1997) – “Burroughs then explores various configurations of the word virus, mainly theological (the Fall from Eden) and media/political (the Watergate scandal), before explaining that once it has accessed the cell, viral infection enters its third and final step, the production of objective reality: “Number 3 is the effect produced in the host by the virus: coughing, fever, inflammation. NUMBER 3 IS OBJECTIVE REALITY PRODUCED BY THE VIRUS IN THE HOST. Viruses make themselves real. It’s a way viruses have” (2005: 7).” (Patoine 2019) – “And in a sort of natural inflection of the conceptual and process art which immediately preceded us, we turned to the idea of incorporating the commerce of art and the economy of the art world into the art itself: We wanted to be famous, glamourous, and rich. That is to say, we wanted to be artists and we knew that if we were famous and glamourous we could say we were artists and we would be … We did and we are. We are famous glamourous artists.” (Bronson, Copyright, Cash, and Crowd Control: Art and Economy in the Work of General Idea 2003) [2]

[2]

General Idea’s first victim was the myth of the artist as an individual

mastermind, they robed “the romantic notions of pure artistic ‘intentionality’,

and the analytic genius-author” (Kane 2010),

and replaced it by an infected general idea of it, a simulation that soon came

to become an objective reality. In fact, the corporate name of General Idea was

the perfect viral method to live off the art world like parasites who infected

the mainstream cultural economy with their glamourous mutations. Thus, the

artist became a stage for constant collaboration, infiltration, simulation,

stretching, performing, mailing, hosting, and participating of people that

otherwise wouldn’t have had being welcomed into the art world. Instead of the individual

author, a non-capitalist economy, horizontal and freed from copyright, was General

Idea’s conception of art production, which built their fame and glamour as a

group of artists.

1. Language Virus

“This strategy is considered an adaptive immunity, as the bacteria, when infected by a phage virus, can copy parts of the viral genomic sequence and integrate them inside its own DNA, interspacing these foreign sequences (called “spacers”) between redundant parts of its own DNA (called “CRISPR repeats” or “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats”, discovered by the team of Yoshizumi Ishino in 1987). This integration of copied spacers leads to a co-evolution of the host and viral genomes, allowing the next generations of bacteria, when they encounter the virus, to efficiently identify it, generating RNA molecules that will guide Cas9 to target the viral DNA sequences originally copied, to splice them and in so doing incapacitate the attacking bacteriophage (Yin 2012). Burroughs uses a similar strategy: his texts use the written word (the virus) against itself, cutting its stereotypical sequences (syntax, narrative) to disable it.” (Patoine 2019) – “Following Burroughs’s fictionalized example, we began with projects through the mail and then graduated to newsmagazine format to perfect our method. We saw FILE Megazine as a parasite within the world of magazines distribution, positioned to infect newsstands, schools and libraries in urban centres. Our familiar, homey, LIFE-like format belied its viral content: images emptied of meaning and filled with our own perverse content of metamythologies, transgressed borderlines and alien consciousness, designed to take hold of the subconscious and infiltrate. At the same time, FILE was a connector, an empty space we offered to our friends; it represented a nongeographical community. LIFE was the perfect model to simulate: assembled almost entirely of images being groomed as media myths, it was an available format that lent itself to appropriation.” (Bronson, Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus: General Idea's Bookshelf 1967-1975 1997)

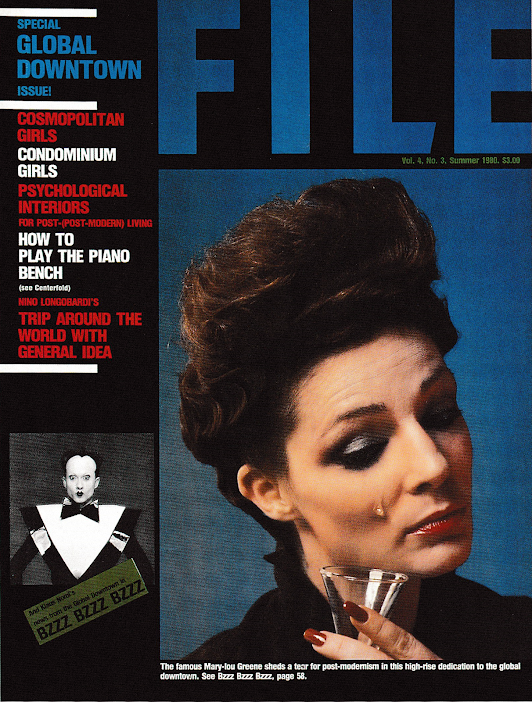

FILE Megazine (Vol. 4, no. 3, summer 1980). 1980. “Special Global Downtown Issue”. Web offset periodical, 64 pp. plus cover, black-and-white reproductions, and spot colour: 355 x 280 mm. Edition of 3000. Published by Art Official Inc., Toronto.

2. Image Virus

“For a virus to be effective, it has to keep adapting to its host. GI occupied the existing infrastructure and created audiences by means of radio invitation, correspondence art, and their distribution outlet and collection centre, Art Metropole. … Manipulating the Self (1970) asked participants to send in pictures of themselves wrapping an arm around their head.” (Busby 2003) – “In this exhibition you can see how the 1971 Pageant grew out for our involvement with mail art, with projects that utilized the mail system, asking friends and artists to respond to a mailing, and using the response to generate a project (an event, a publication) in which they could again participate: a sort of cultural biofeedback … But finally it was an event designed to television, in which the audience became the performer, the mythical pageant moments (‘May I have the envelope, please!”) were assembled into a collage of meta mythical intent, and the art world system was stripped of pretense and bathed in irony.” (Bronson, Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus: General Idea's Bookshelf 1967-1975 1997) – “Ultimately General Idea’s interest in systems and our identity as parasites led us to establish our own universe of an art world within our artmaking: we were at once theoreticians, critics, artists, curators and bureaucrats, the penultimate shape-shifters. The metastructure of our artmaking included not only the studio, the artist and the artwork but also the museum, the archive, the gallery shop and even the mass media (our own television, our own magazine) as a sort of armour or carapace we wore for invading the art world.” (Bronson, Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus: General Idea's Bookshelf 1967-1975 1997) – “The Colour Bar Lounge was the mythical bar at the Miss General Idea Pavillion where new drinks were concocted in test tubes and meant to induce artful research: ‘These cocktails are the medium in which a culture is grown and introduced to the host … and everyone is a host at the Colour Bar Lounge.’ Implicating the audience as host GI hoped that their art elixirs would have the same potency as the pharmaceutical industry in their ability to get under the skin” (Busby 2003) – “The true problematic of the Boutique was revealed when it began to be exhibited in museums. Some museums were unable to sell from the Boutique because of conflicts with their museum shops; most were unwilling to sell from the Boutique because of the heresy of commerce infecting the pure white cube. … Most recently, the Museum of Modern Art in New York exhibited the Boutique with the multiples under Plexiglass, so they could not be touched, in a sort of castrated and purely archival state. I think of this as the ultimate revenge of the artwork that dared to expose the hypocrisy of the museum.” (Bronson, Copyright, Cash, and Crowd Control: Art and Economy in the Work of General Idea 2003)

3. Human Immunodeficiency Virus

“A virus thrives because of its ability to mutate according to the conditions of its host. From the beginning, General Idea was like a virus, infiltrating popular culture and occupying a grand discursive space.” (Busby 2003) – “In the 1980s, when the word virus came to have a more literal intervention in our lives, when HIV opened the door to a host of viral infections in Jorge’s and Felix’s bodies, we revised these methods to suit the times: we injected the image of our AIDS logo into the lifeblood of the communication, advertising and transportation systems – as billboards, electronic signs, posters, magazine covers, even a screen saver – to spread, virus-like through the public realm.” (Bronson, Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus: General Idea's Bookshelf 1967-1975 1997) – “They were aware of the cachet of the portrait in popular culture, and created versions that ranged from studio set-ups for magazine covers to pseudo-scientific mug shots. The use of the portrait continues in Bronson’s practice. A few hours after Felix Partz died, AA photographed him propped up in bed on multi-coloured pillows, surrounded by the things that made him happy. He looks comfortable with his TV remote close at hand. But this is not a comfortable image to look at, made even less so by its larger-than-life billboard size.” (Busby 2003)

# Now what? – “For many years we used commercial fabrication of works to avoid the fetichism of the artist’s hand, of the mark of the individual genius. Similarly, our corporate name belied individual authorship. For the entire twenty-five years of our collaboration, we questioned and played with various aspects of authorship and copyright.” (Bronson, Copyright, Cash, and Crowd Control: Art and Economy in the Work of General Idea 2003) – “By overthrowing the language virus and its demands for efficacy, production and reproduction, The Wild Boys dreams of overthrowing the colonial world order, allowing Western Europe and North America to be saved through the destruction of its “coded” civilization by hordes of erotic wild boys from Africa and South and Central America (1971: 138).” (Patoine 2019) – “In the final words of the book, ‘… may you allow WE 3 to live forever with you, together in your world of art; always, always, always…’” (Busby 2003)[3]

[3] By incorporating the distribution and communication forms of mass media into their creative processes, General Idea was able to infiltrate a new artificial myth about the role of the artist into the cultural economy. General Idea’s viral methods infected Nort American coded values of ownership, individuality, commerce, and control by spreading their infection into the art world and the public realm, thus ironizing and exposing contemporary consumer culture’s hypocrisy about North American capitalist order. In these terms, the notion of virus is understood as a weapon which power resides on its ability to mutate, simulate, copy, connect, cut, and create new realities which disable the mainstream culture as well as the art world. The three faces of the virus here exposed demonstrate the malleability of this methodology, first in its capability to act against its host by cutting its stereotypical sequences and disabling it, then spreading the infection by including new participants to perform into it, and finally producing an objective reality by showing to others its glamourous effect on the host, which is, by this moment, undeniable. Still weak though, as it contains a contradiction, the apparent white man’s fascination for the mechanisms of marketing, which is “today’s main instrument of social control”. In fact, General Idea’s attraction towards the mechanisms of the cultural economy might be the reason why the MOMA was able to finally castrate the Boutique’s attempt to expose its hypocrisy (Deleuze 2006). Therefore, to compensate this weakness, it would be interesting to expand this conversation with Legacy Russell’s manifesto on Glitch Feminism, which takes advantage of modern viral methods to offer an actual vision on issues like gender, remixing, the internet, race, surveillance, colonialism, and the body, among others, aiming “to corrupt data and fuck up the machine to tear it all down as a new beginning” in the XXI century (Russell 2020).

Bibliography

Bronson, AA. 2003. "Copyright, Cash, and Crowd Control: Art and Economy in the Work of General Idea." In General Idea Editions: 1967-1995, edited by Barbara Fischer, 24-27. Toronto, Ontario: Blackwood Gallery, University of Toronto at Mississsauga.

Bronson, AA. 1997. "Myth as Parasite/Image as Virus: General Idea's Bookshelf 1967-1975." In The Search of the Spirit: General Idea 1968-1975, by Art Gallery of Ontario, 17-20. Toronto, Ontario: Art Gallery of Ontario.

Busby, Cathy. 2003. "Ramaining Viral." In General Idea Editions: 1967-1995, edited by Barbara Fischer, 270-272. Toronto, Ontario: Blackwood Gallery, University of Toronto at Mississauga.

Deleuze, Gilles. 2006. "Post-scriptum Sobre las Sociedades de Control." Polis, Revista de la Universidad Bolivariana de Chile, 0. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=30551320.

Kane, Carolyn L. 2010. "Programming the Beautiful: Informatic color and aesthetic transformations in early computer art." Theory, Culture & Society, 73-93.

Mandic, Jelena Z. 2015. "The Priest They Called Him: The Experimental Work of William Burroughs." Filolog (University of Banja Luka, Faculty of Philology) (12): 164-172. doi:https://doi.org/10.7251/fil1512164m.

Patoine, Pierre-Louis. 2019. "William S. Burroughs and The Wild Boys Against the Language Virus: A Biosemiotic Guerrilla." Recherches sémiotiques / Semiotic Inquiry, April, Biosemiotics. Tome 2 ed.: 117-133. https://doi.org/10.7202/1076228ar.

Russell, Legacy. 2020. Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto. London, New York: Verso.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario